Microsoft Ignite lands in San Francisco on November 18–21, 2025, and the data stack is poised for some long‑awaited “flip the switch” moments. If even half of the current previews in Fabric and Power BI cross the finish line, day‑to‑day analytics work gets simpler, faster, and easier to govern. Here’s what we’ll be watching most closely.

Continue reading “Five GA Moments We’re Watching for at Microsoft Ignite 2025”Author: Jason Miles

From TechEd to Ignite to FabCon: Why Showing Up Still Shapes the Tech We Build

If AI can summarize the keynote in seconds, why bother getting on a plane? Because the conversations that redirect roadmaps and careers still happen in the hallway, not the livestream. I’ll trace Microsoft Ignite’s arc, make the case for in‑person connection in a technical world, and end with a simple invitation: plug into the community now—and meet us at FabCon (now including SQLCon).

Continue reading “From TechEd to Ignite to FabCon: Why Showing Up Still Shapes the Tech We Build”Pre‑Ignite 2025: The State of the Data Platform

What to watch in the eight days before Ignite—and how to translate the signals into architecture bets that age well.

Continue reading “Pre‑Ignite 2025: The State of the Data Platform”Agile Needs a Spine: Aligning Dates, Deliverables, Objectives, and KPIs

A recent conversation with a colleague reminded me of how important applying structure to an agile project team is. Most industries can’t take, to quote the old Blizzard line, the option to release it “when it’s ready,” because they’ve made commitments to customers or other parts of the business.

Agile frees teams from big-batch planning, but it doesn’t free them from consequences. When dates, deliverables, objectives, and KPIs drift apart, you get motion without momentum—busy sprints, delayed value, and vague success. In this piece, I’ll show why alignment across these four anchors is the operating system for agility, how to keep it lightweight, and why you can’t—and shouldn’t—abandon traditional project management entirely.

Continue reading “Agile Needs a Spine: Aligning Dates, Deliverables, Objectives, and KPIs”Making Schema Change Boring: A Short History—and How Microsoft Fabric’s Medallion Lakehouse Bakes It In

Schema changes have always been risky because a schema isn’t just columns—it’s the interface between data producers and data consumers. Historically, that interface was rigid, which made any change expensive. Modern lakehouse design solves the problem structurally: a Medallion architecture separates where variation is tolerated (Bronze) from where commitment is made (Silver) and relied upon (Gold). In Microsoft Fabric, those roles map cleanly to Lakehouse, Warehouse, and Power BI’s semantic layer, with governance and domain‑oriented (data‑product) design tying it all together. By the end, you’ll see why schema evolution is both inevitable and manageable—and how Fabric builds that manageability into the platform.

Continue reading “Making Schema Change Boring: A Short History—and How Microsoft Fabric’s Medallion Lakehouse Bakes It In”Data Literacy, Citizen Analysis, and the Shift to a Data‑Enabled Culture

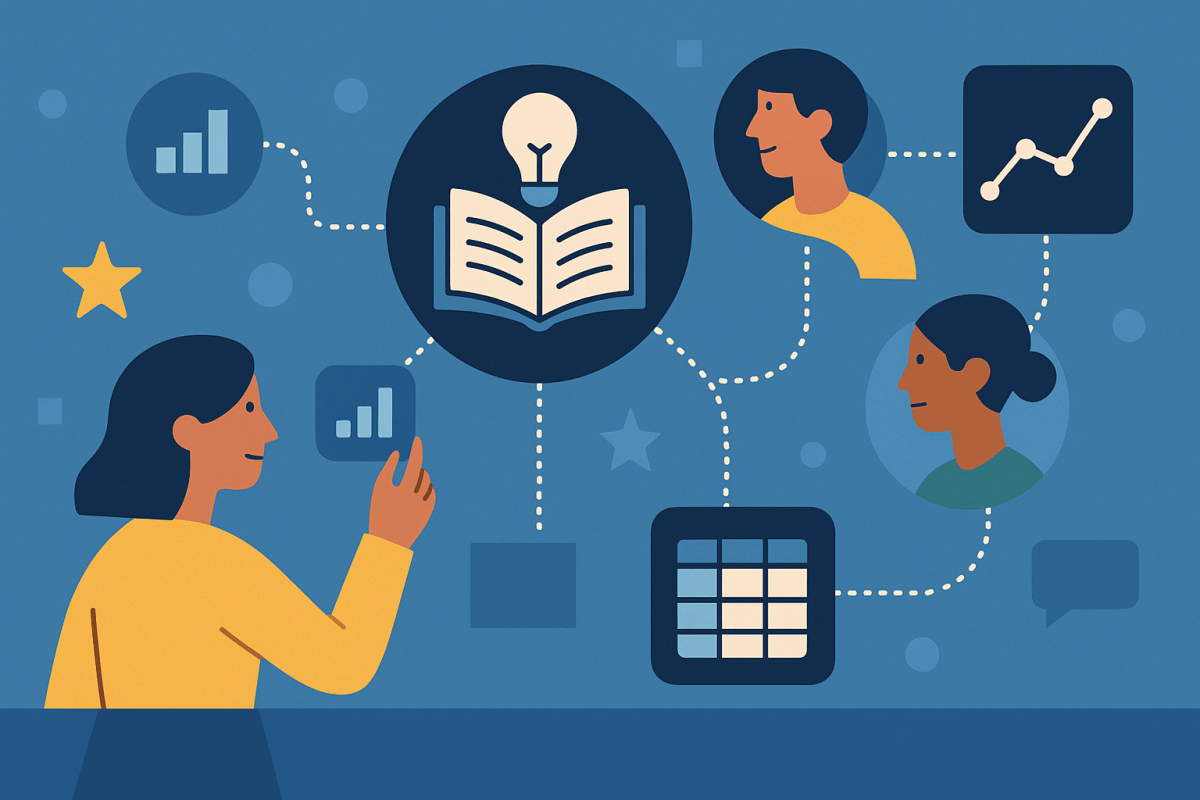

I’ve never been fond of the phrase data‑driven. It can imply that people should surrender the wheel to whatever the chart says. I prefer data‑enabled: a culture where evidence is visible, disputable, and useful—where humans steer and data is the headlight, not the driver. That shift doesn’t start with a platform; it starts with literacy, and it grows when more people can do a little analysis for themselves.

Continue reading “Data Literacy, Citizen Analysis, and the Shift to a Data‑Enabled Culture”Beyond Boxes and Lines: Designing for the System of Systems Your Software Must Live In

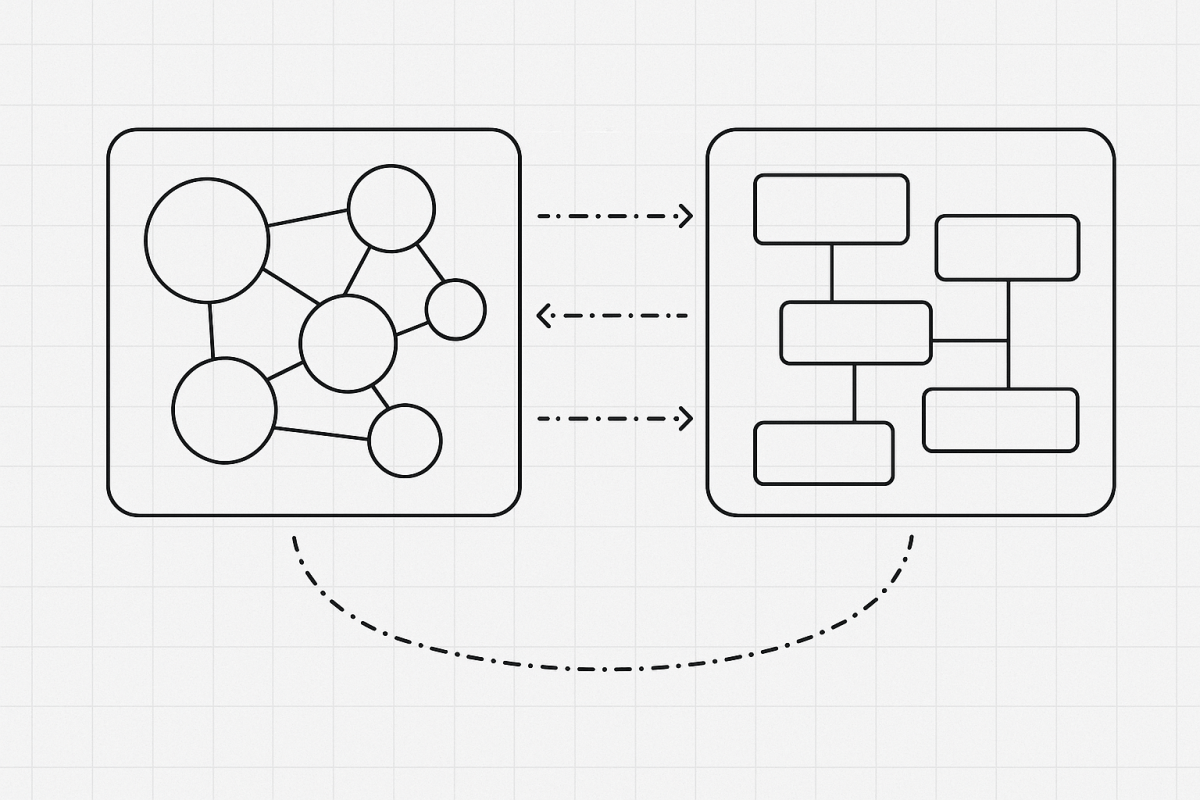

Architecture diagrams look clean—until they collide with the place your system actually lives. That place is not just “production.” It’s your organization: a dense system of systems made of teams, processes, policies, budgets, and tools. The primary reason to understand the organization in which a system will reside is precisely these systems. Your software must integrate with them as surely as it integrates with databases and queues.

I’ll make one argument three ways. First, I’ll define system of systems and show why the org is part of the runtime. Next, I’ll connect business architecture to systems architecture so strategy and structure reinforce each other. Finally, I’ll revisit Conway’s Law—how to use it deliberately and how it can quietly work against you. Then I’ll close with a practical loop you can run before you write code.

Continue reading “Beyond Boxes and Lines: Designing for the System of Systems Your Software Must Live In”Review: Software Requirements (3rd Edition) — the best light for a “dark art”

If software requirements really are a “black art,” Software Requirements (3rd Edition) is the field guide that turns on the lights. Karl Wiegers and Joy Beatty’s update for Microsoft Press remains the most practical, end‑to‑end treatment of requirements work I’ve seen—thorough enough for architects and business analysts, yet approachable enough to hand to a junior developer or data engineer without scaring them off. The 3rd edition (published August 15, 2013) is part of the Developer Best Practices series and runs a hefty 600+ pages, but it’s organized so you can dip in by problem, not just read cover to cover.

What the book actually covers (and why it matters)

Rather than treating “requirements” as just a bulleted wish list, the book walks the full lifecycle: defining business objectives and stakeholder goals, eliciting and analyzing needs, documenting them clearly, setting priorities, validating them, managing changes, and improving the process over time. The table of contents is unusually actionable: you’ll find chapters on Writing excellent requirements, Specifying data requirements, First things first: Setting requirement priorities, Risk reduction through prototyping, and a concluding set of chapters on management, change control, tools, and process improvement. This structure is why the book adapts well to many team shapes—product‑led, BA‑led, or engineering‑led.

What’s new in the 3rd edition

The refresh isn’t cosmetic. It adds new chapters and depth where modern teams need it most:

- Data work gets first‑class treatment in “Specifying data requirements”—a big win for analytics and data engineering projects that too often treat schemas and quality rules as afterthoughts.

- Writing high‑quality functional requirements and requirements reuse get dedicated chapters, codifying what “good” looks like and how to avoid rewriting the same specs every quarter.

- Special project contexts have their own playbooks: agile, enhancement/replacement, packaged/COTS, outsourced, business process automation, business analytics/reporting, and embedded/real‑time.

- The agile chapter is pragmatic: it doesn’t try to cram user stories into old‑school templates; instead it shows how to blend discovery, backlog management, and validation techniques so teams can be lean without being sloppy.

Why developers and data engineers should read it

Requirements are a “dark art” every developer and data engineer needs to understand—and this edition meets that moment. Two examples:

- From user need to testable behavior. The chapters on documenting, visualizing, and validating requirements keep the focus on clarity and testability, which shortens the path to code and automated checks. If you’re used to triaging ambiguous tickets, the “writing excellent requirements” and “validating the requirements” material pays for itself quickly.

- Data‑heavy projects. Between “Specifying data requirements” and the dedicated “Business analytics projects”chapter, it treats data models, quality attributes, lineage, and reporting behaviors as first‑class concerns—ideal guidance for modern lakehouse/warehouse and ML‑adjacent work where “the requirement” is as much about datasets, SLAs, and semantics as UI.

The strengths that make it gift‑worthy

- Field‑tested checklists and patterns. You don’t only get principles; you get templates, self‑assessments, and a troubleshooting guide you can use in the next backlog grooming or discovery session. Those appendices—Current requirements practice self‑assessment, Requirements troubleshooting guide, and Sample requirements documents—are pure leverage.

- Balanced tone. It respects both plan‑driven and agile contexts. The authors show how to scale the rigor up or down without lapsing into ceremony for ceremony’s sake.

- Breadth without hand‑waving. The “special project” chapters keep you from reinventing the wheel when constraints change (enhancement vs. greenfield, packaged vs. custom, embedded vs. information systems).

A few quibbles (so you know what you’re getting)

- Document‑first bias in spots. Some examples still assume a document‑centric flow. That’s not wrong, just heavier than many teams prefer. Pairing the guidance with story mapping, lightweight specs, and executable examples keeps it nimble.

- Not a substitute for domain discovery. It teaches you how to discover and specify; it won’t do your product thinking for you. You still have to bring domain sense and stakeholder time to the table.

How to use the book (a practical reading path)

For developers or data engineers who want the fastest return:

- Ch. 1–4 for the foundations and roles.

- Ch. 10–12 & 14 to document clearly (text + visuals + nonfunctional qualities).

- Ch. 16–18 to prioritize and validate before you over‑invest.

- Ch. 13 & 25 if you’re in analytics/data engineering.

- Ch. 20 for agile projects.

- Skim the self‑assessment and troubleshooting guide to identify your team’s weakest links and fix those first.

Bottom line

On the same shelf as Code Complete, Framework Design Guidelines, The C++ Programming Language, and K&R, Software Requirements (3rd Edition) earns its keep by turning fuzzy intent into testable, buildable, and maintainable software behavior—without pretending there’s only one right way to do it. If you mentor younger engineers, this is an easy book to pass along: it’s comprehensive, concrete, and relentlessly practical. For the “dark art” of requirements, this is the light you want.

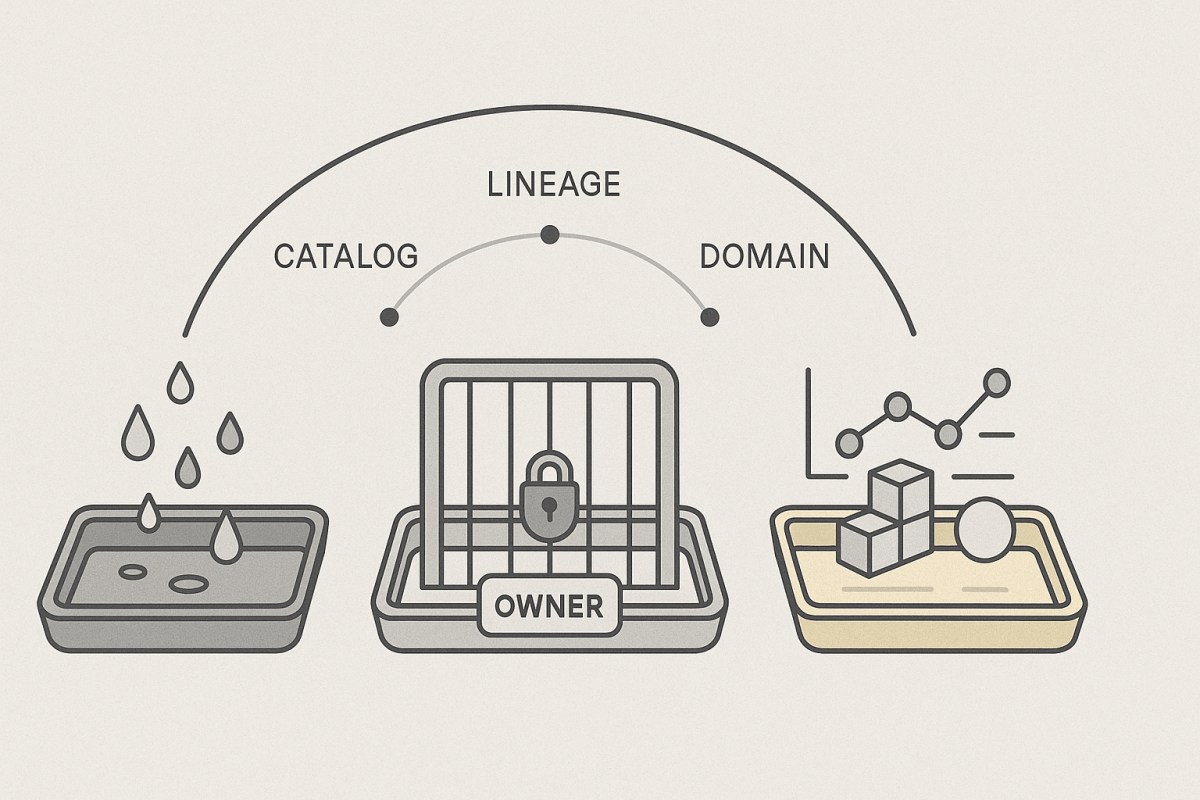

Build Products, Not Ponds

If you agree that data should be judged by the decisions it improves, the way you build with data changes. You stop trying to pour every table from every system into one giant lake and assume value will appear later. Instead, you ship small, finished data products that help with one decision at a time. The first approach optimizes for storage. The second optimizes for outcomes.

Think of cooking. Stocking a huge pantry doesn’t guarantee a good dinner. A clear recipe, the right ingredients, and a plate on the table do. Data products are the recipes and the plates; “ingest everything” is the overflowing pantry.

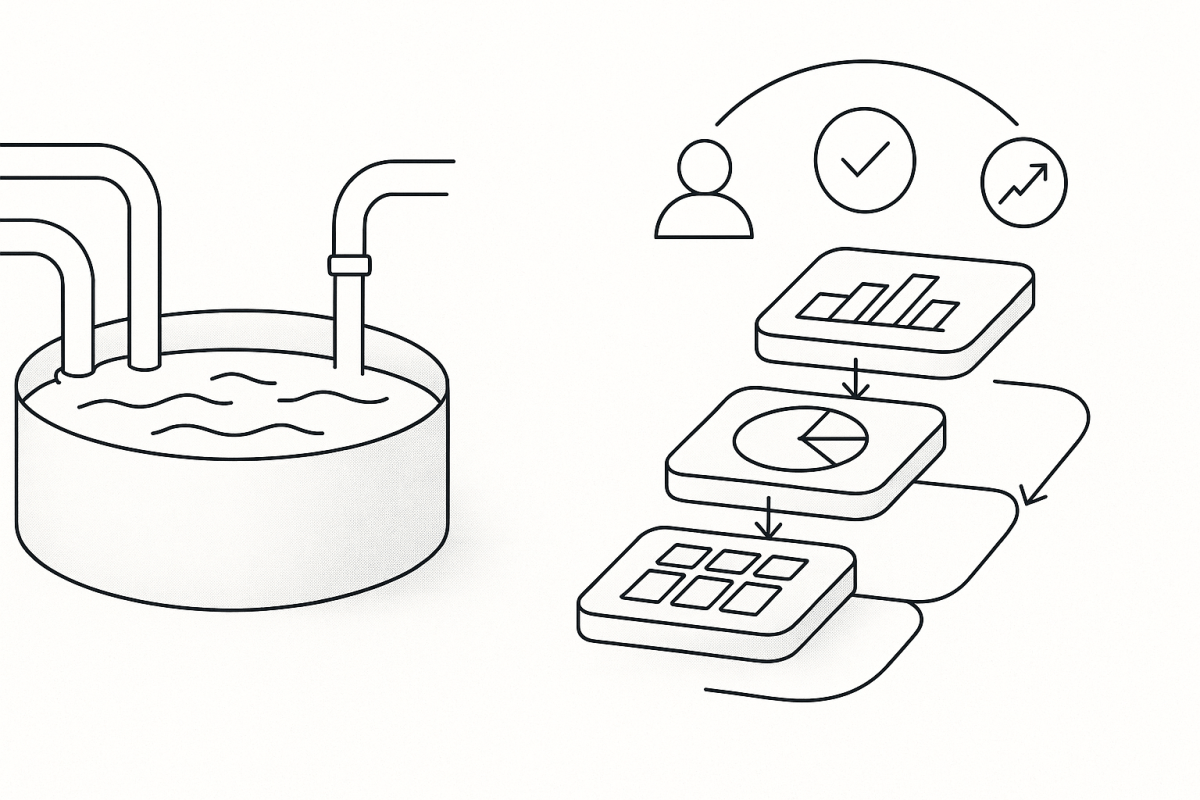

Why “ingest everything” feels safe—and why it isn’t

Pulling all sources into one place sounds responsible. You can say, “It’s all there. We’ll use it soon.” The trouble shows up later. Definitions drift because no one agreed on them where it matters—at the point of use. Different teams read the same column in different ways. Security rules live in documents instead of inside the data itself. And because nothing is built for a specific decision, real users never know when it’s “done,” so projects swim in circles.

Central storage isn’t the villain. It just isn’t the hero. Storage alone rarely changes a decision. Decisions change when real people can see something that matters, trust what it means, and act on it—reliably, without a tour guide.

What a data product is (in plain English)

A data product is a small, finished thing a person or system can use without you standing next to it. It has a clear job: “help a claims adjuster spot risky cases,” “help the street team pick tomorrow’s routes,” “help a planner see late parts before the shift starts.” It takes known inputs and produces a known output. It makes promises about freshness (“updated every two hours”), availability (“there when you need it”), and meaning (“this field always means X”). It has a named owner who is responsible for keeping those promises. And it has guardrails built in—who can see it, what gets logged, and what happens when something goes wrong.

That’s it. Not fancy. Just usable, understandable, and accountable.

Promises, not pipelines

Most data work stops at “we built the pipeline.” Users don’t buy pipelines; they buy promises. A promise is specific enough to measure: “New transactions appear within 120 minutes.” “Coverage includes 95% of active accounts.” “Anyone in the fraud unit can try it without asking an engineer.” When promises are clear, two things happen. First, users know what to expect and can plan around it. Second, the business can actually price the promise. If the product gets fresher, we respond faster. If definitions are tighter, we argue less. If the surface is self‑serve, we need fewer handoffs. Those are dollars and hours, not opinions.

A simple way to tell if you have a product: if a new team can use it tomorrow with nothing more than a short read‑me, you’re there. If they need a standing meeting, you’re not done.

How product‑first building makes value visible

When you build for one decision, you’re forced to be specific. Who is the user? What do they need to see? When do they need it? How will we know it helped? Those questions become the product’s promises. Because the promises are explicit, you can connect them to outcomes. Faster refresh means fewer missed opportunities. Clearer definitions mean fewer rework loops. Automation at the last step means shorter cycle times. Now “data quality” isn’t a sermon—it’s part of the business case, with visible cause and effect.

This clarity also keeps risk in the open. A product has a boundary. You can say who is allowed to use it, how access is recorded, and what’s masked by default. If there’s sensitive information, the protection isn’t a side note; it’s part of the design. Smaller, clearer boundaries shrink the chance that one mistake becomes a big incident.

Why small, composable products reduce risk

Over time you will want to build bigger things. The safest way to grow is to compose new products from ones that already work. Think LEGO bricks: each brick is simple, but if it clicks and holds, you can build a lot without surprises.

Picture an engagement product built from three pieces that already proved themselves: an identity and permissions product that tracks who someone is and what they’re allowed to see; a customer‑events product that records important actions in one clean stream; and a propensity product that scores the likelihood someone will respond. When you combine them into “next best action,” you aren’t multiplying unknowns—you’re stacking known quantities. If the combined product struggles, you can see which promise failed and fix that piece, instead of digging through a tangle of pipelines.

The same pattern works elsewhere. In a plant, a sensor‑signals product, a maintenance‑history product, and a parts‑catalog product come together as predictive maintenance. In a city, an asset registry, a 311 requests stream, and a routing layer become smarter street repairs. Big results, smaller unknowns.

The quiet costs of “boil the ocean”

Trying to “do it all” up front sends three quiet bills.

The first is definition drift. When meaning isn’t settled where data is used, teams settle it later, in production, under pressure. That’s where mistakes become public and expensive.

The second is one‑off work. Without product surfaces, every new consumer is a custom project. Engineers become translators; users lose patience; everyone assumes data work is slow.

The third is governance by inbox. Policies exist, but since nothing has clean boundaries, approvals and exceptions bounce between people. You feel slower, not safer.

None of these show up on day one. All of them show up on the balance of the year.

How the right platform appears (instead of arriving by forklift)

There is still a platform in a product‑first world. It just emerges from repeated wins rather than being invented ahead of time. After a few products, the patterns are obvious: the same way to handle permissions, the same way to describe a field, the same way to record where data came from, the same way to release a change. Those pieces become the platform because they’ve proven they save time and reduce mistakes. You standardize only what deserves it, and you keep the platform small and helpful because it grew out of actual use, not a whiteboard.

A good test is this: if a platform feature can’t point to three live products that needed it, it’s not a platform yet—it’s a hunch.

A short before‑and‑after story

In one version of the quarter, a team pulls six systems into a lake, builds a lovely catalog, and shows a demo that answers almost any question—as long as the author is in the room. Little changes for the people who make decisions every day.

In the other version, the team ships a simple claims‑triage product for the fraud unit. It refreshes every two hours, explains why it flagged a case, and anyone on the team can try it. Adjusters use it the first week; the lift is small but real. Two weeks later, the team tightens the refresh time and publishes examples for another unit. By the end of the quarter, three products are live. The common pieces—permissions, shared field definitions, and an audit trail—have been pulled into a tiny starter platform because they obviously help. Quarter two doesn’t start from zero; it starts from working bricks. New products assemble faster, risks are clearer, and value appears earlier in the calendar.

Only one of those stories is easy to defend when budgets tighten.

Switching without drama

If you already have a big lake, don’t throw it out. Pick one decision and draw a product boundary on top of what you have. Ship the smallest end‑to‑end slice that helps a real user—something they can open, understand, and use without you in the room. Write down the promises you actually met. Measure whether people used it and whether it helped. Then do it again with the next decision. After a few cycles, you’ll know which parts of your current stack deserve to be standardized and which parts should be retired.

Two habits make this work. First, keep the feedback loop short. Talk to users weekly, and let what they do (not just what they say) shape the next slice. Second, treat your promises like product features. If freshness is missed or meaning is unclear, fix the product before adding new sources. You’re building trust, not just tables.

How to know you’re on the right track

You don’t need a dashboard of dashboards. A few simple signals tell you if product‑first is working. New teams can start using a product in a day. The first “win” for a product happens within weeks, not quarters. When something breaks, you can find the owner and the logs within minutes. And perhaps the most honest sign: your users bring you ideas you didn’t pitch to them—because they finally see how to turn an idea into something they can use.

Common worries, answered plainly

“What about standards?” You’ll get better standards by extracting them from things that worked than by writing them in a vacuum. Real use trims wish lists into a few rules people follow.

“Won’t we duplicate effort?” Some duplication is the price of speed at the start. The moment two products solve the same problem well, you pull the common solution into the platform. Now you’re standardizing success, not opinions.

“Isn’t this risky?” It’s the opposite. Smaller products shrink the blast radius. Composed products build on known parts. You learn earlier, fix cheaper, and avoid betting the whole quarter on one giant merge job.

Conclusion

Data changes decisions, not storage quotas. Product‑first design keeps you close to the decision: clear purpose, clear promises, clear guardrails, clear results. Ingestion‑first bets that usefulness will appear once the plumbing is perfect. Sometimes it does, but it’s late and costly.

Start small and ship something someone can use without you in the room. Let quality and safety be features, not footnotes. Then compose. Each product lowers uncertainty. Each composition raises your ceiling without raising your risk. That’s how you build a portfolio you can rank, fund, and defend—and a platform that grows out of wins instead of getting in your way.

Releases Imply Requirements

In a recent post, I argued that a real release is a declaration—a line in the sand that says, this is the version we stand behind. A declaration begs a follow‑up: what exactly are we declaring? The honest answer is: requirements. A release without requirements is just a pile of diffs; a release grounded in requirements is a promise we can audit, test, and keep.

This is where classic software requirements work—yes, the unglamorous kind—earns its keep in data and analytics. If releases create accountability, requirements make that accountability usable.

Continue reading “Releases Imply Requirements”